What is a Pathogen?

Plant Pathogens are living things that use a plant’s resources for their own survival, often causing harm to the plant in the process. People sometimes mistake plant pathogens for plant diseases (1). While it is true that plant pathogens often lead to plant diseases, it is important to note that plants can have pathogens but not be diseased (1). This is because of the disease triad. The disease triad states that for a plant to become diseased, the plant host, the pathogen, and the environment (ie, the weather) must be conducive to disease (1). For example, if the weather is very rainy, it may stress the plant host, while simultaneously allowing fungal diseases (such as Sclerotina) to be more vigorous. This leads to a situation where two crops with the same amount of initial pathogen have drastically different disease outcomes. On the other hand, two crops exposed to the same weather conditions but with different pathogen loads will also likely experience a different disease outcome. To date, there are many ways to measure both the susceptibility of the host plant and to quantify how the environmental conditions either promote or suppress disease. PathoScan aims to let you understand your field’s pathogen load on your terms, allowing you to use this information to make smarter growing decisions.

There are many different types of pathogens, including traditional microscopic germs, such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, as well as larger living organisms, including nematodes and parasitic plants like mistletoe. Below is a list of the important types of microscopic pathogens and some key features of each.

Fungi are microorganisms that often require wet environments. At a cellular level, fungi are more related to plants and animals than to bacteria. Because of this, they are much more complex and can often have complicated life cycles that require multiple host plant species to complete. Fungi are built to survive harsh environments. In unfavourable conditions, some Fungi, such as Sclerotina, can form hard structures called sclerotia. These cacoons preserve the cell until conditions are once again favourable for disease. Sclerotina also makes complicated reproductive structures that launch spores into the air, allowing them to be carried in the wind.

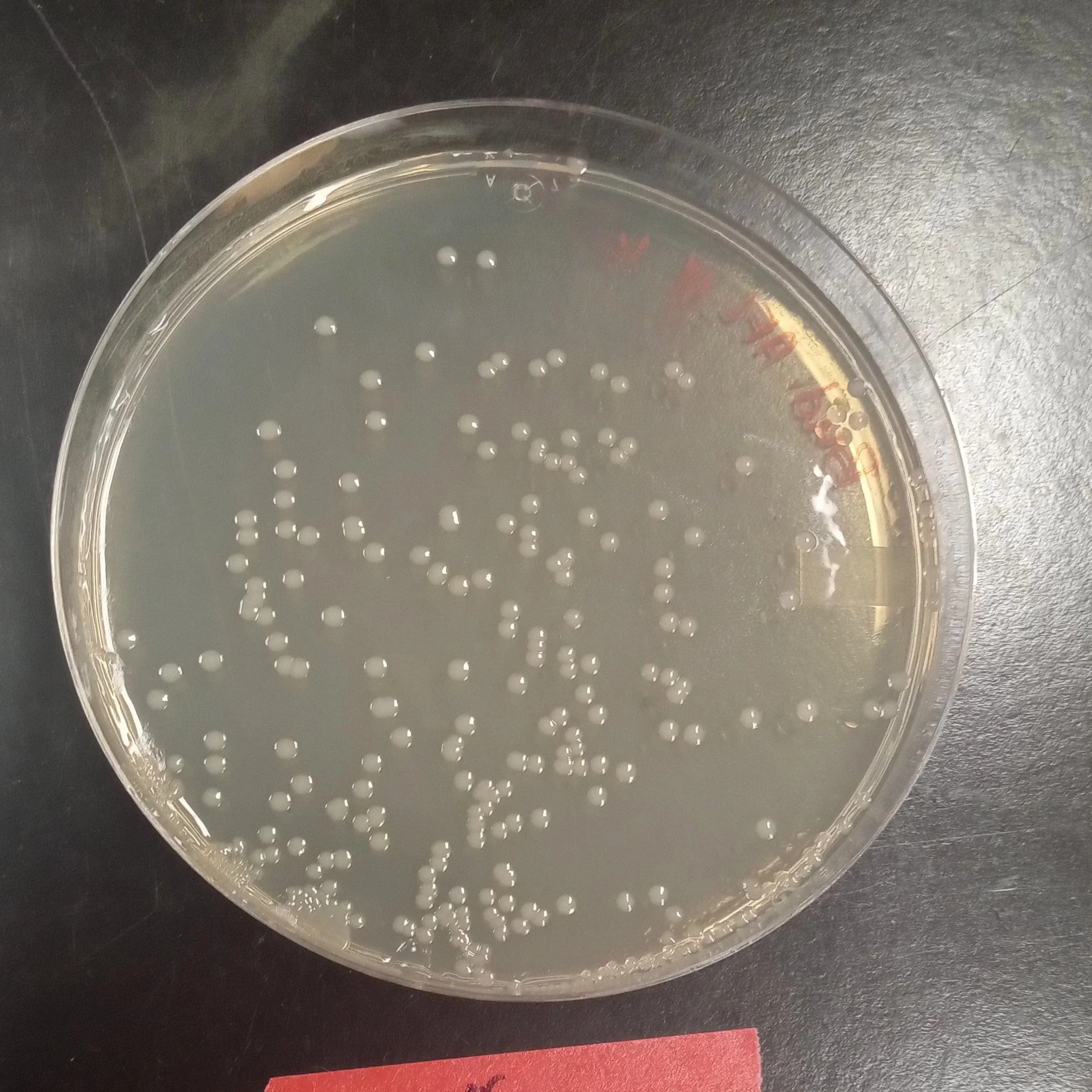

Bacteria (shown in the image) on the other hand, are small cells that live alone and often reproduce asexually. This is a very fast method of reproduction and allows bacteria to adapt to antibacterial treatments much faster than fungi can adapt to antifungal treatments, all else being equal. It is important to note that not all bacteria are pathogens. For example, bacteria allow for nodulation of peas. Additionally, bacteria in the soil often also produce natural antifungal compounds that can suppress fungal pathogens such as Fusarium solani (experimental data).

1. U.M. Aruna Kumara, P.L.V.N. Cooray, N. Ambanpola, N. Thiruchchelvan. (2022). Plant-pathogen interaction: Mechanisms and evolution. Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, Trends of Applied Microbiology for Sustainable Economy. Pages 655-687, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91595-3.00025-2.

-

Add a short summary or a list of helpful resources here.